Providing people with more choices in housing, shopping, communities, and transportation is a key aim of sustainable growth. As more communities adopt sustainable growth principles, the benefits of linking transportation, the workplace, and housing are becoming clearer. Communities are increasingly seeking these choices, particularly a wider range of transportation options, in an effort to improve overwhelmed transportation systems. Even though most Americans still use a personal automobile for the majority of their trips, interest in improving all forms of transportation, including mass transit, biking, and walking, is on the rise. In a 2003 poll sponsored by the American Automobile Association (AAA) and the American Public Transportation Association, 71% of the adults polled stated that it was important to have both good roads and viable alternatives to driving, including better support for bicycling and walking. Another poll found that increased public investment in public transportation would strengthen the economy, create jobs, and reduce traffic congestion and air pollution. Both polls cited consistent support for investing in a variety of transportation options.

Transportation plays a critical role in where and how cities, counties and communities develop and grow. Accessibility to home, work, community centers, stores, businesses, and industry are key components of any community’s growth and development patterns. In fact, access to a particular place in large measure determines it range of potential or appropriate uses. Transportation has profound impacts on housing, employment, efficiency, quality of life and social equity. By recognizing the cross-cutting effects of transportation investments, local governments can use transportation as a tool to attract and direct desirable development and conservation activities.

The science of traffic management and predication has begun to catch up with what citizens have observed for years now: new road capacity fills up almost as fast as it is constructed. Known in transportation circles as “induced demand,” studies now that as large new roads are built people increase their driving to take advantage of the new infrastructure. Some studies suggest that between 60 and 90 percent of new road capacity is consumed by new driving within five years of the opening of a major road. In the short term, people may switch from using transit and carpools to traveling the new road, and in the long term, with the increased accessibility of the surrounding land, development patterns shift to create more growth and new traffic in the area. In regions around the county, travel forecasters show that the continuation of current policies and practices is unlikely to alleviate congestion.

In response, communities are beginning to implement new approaches to transportation planning, such as better coordinating land use and transportation; increasing the availability of high quality transit service; creating redundancy, resiliency and connectivity within their transportation networks; and ensuring connectivity between pedestrian, bike, transit and road facilities. In short, they are coupling a multimodal approach to transportation with supportive land-use patterns that create a wider range of transportation options.

Local officials must balance the need for better transportation and related facilities in challenging financial environments. Transportation professionals are looking for creative policies that make the best use of existing transportation investments and systems that maximize both transportation and economic performance. This is where sustainable growth policies can provide an array of solutions. For example, many localities have teamed with transit agencies to adopt special planning and zoning districts for transit stations in order to increase ridership and raise revenue.

Intermodal Transportation Hub, Fort Worth, Texas

Transportation officials and localities are also beginning to seek input from a wider array of community members. Among these community members, unexpected alliances are forming to support better transportation and community development. The Boone County Smart Growth Alliance in Missouri, a partnership of environmental, community and rural conservation groups, grants Smart Growth Awards to recognize development projects which take into account existing transportation infrastructure and promote walkable areas. Spurred by transportation problems, the business communities in Atlanta, Georgia; Chicago, Illinois; and California’s Silicon Valley have led the way implementing smarter growth. As the policies in this chapter suggest, both public-and private-sector strategies offer opportunities to create a range of transportation choices

Transportation officials and localities are also beginning to seek input from a wider array of community members. Among these community members, unexpected alliances are forming to support better transportation and community development. The Boone County Smart Growth Alliance in Missouri, a partnership of environmental, community and rural conservation groups, grants Smart Growth Awards to recognize development projects which take into account existing transportation infrastructure and promote walkable areas. Spurred by transportation problems, the business communities in Atlanta, Georgia; Chicago, Illinois; and California’s Silicon Valley have led the way implementing smarter growth. As the policies in this chapter suggest, both public-and private-sector strategies offer opportunities to create a range of transportation choices

Strategies that can address the transportation choices that our region needs are varied. Some of the strategies are more regional in nature, while others may be applied at the community or project level. A combination of strategies that can be implemented at various levels is needed because the transportation issues our region faces cannot be addressed by just one agency or community. A consolidated effort utilizing a variety of strategies is required. The following is a list of potential strategies that can be used to address this issue.

Provide a Balanced Transportation System that Creates Choices

A balanced transportation system supports a variety of land uses that make it convenient for users to choose multiple modes of transportation. These choices include autos, bicycles, walking or transit options. Successful communities cannot rely upon just one form of transportation to meet the needs of its citizens. Infill and mixed-use development are good examples of ways to encourage balanced transportation systems. By providing a good system of roads, walking paths, and transit, the user then has the opportunity to make a choice of which mode to use.

Optimize ExistingTransportation Systems First

The easiest and quickest way to improve traffic flow is to use the existing transportation systems in a more efficient manner. Typically, these strategies are relatively low in cost but are generally highly effective. Implementing improved signal timing, coordination of existing traffic signals and striping changes to introduce turn lanes are examples.

Prepare Master Plan for Transportation

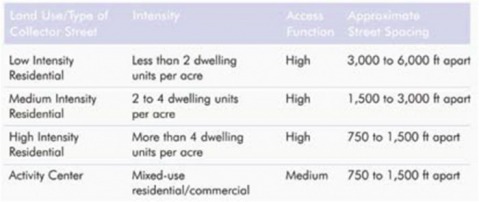

Part of a local transportation planning effort should include a plan for collector streets, especially in intended growth areas. Connected local streets are critical to the transportation network and to active modes of transportation, but just as important is an evenly spaced network of collector streets that provide access from the local streets to the major arterials. Collectors streets carry less traffic, have lower speeds, travel shorter distances then arterials, and help take traffic pressure off of major and local streets. They also provide attractive route alternatives from neighborhoods to major activity centers for motorists, transit, cyclists and pedestrians.

The following graphic and table show examples of collector street spacing based on density.

The following graphic and table show examples of collector street spacing based on density.

Such a plan can provide a mechanism for our areas to protect and provide for key alignments as new development or redevelopment occurs. A collector street plan should be used to preserve and suggest the general location of future connections. As new developments are proposed, planning officials can use the plan to reserve tight-of-way and/or require the construction of new collector streets. In many cases, collector streets can be wholly or partially built by private developers.

Update Plans for Transit, Pedestrian, and Bicycle Infrastructure

A common theme in this time of sustainable growth is the want for more sidewalks, more bike lanes and bike paths, and more greenway/multi-use path connections linking the places where people live with the places that they go to shop, work or play. Not only are such types of infrastructure conducive to cheaper, more efficient, and healthier transportation choices, they are also less expensive to provide than other transportation infrastructure. Recent national surveys have shown that such facilities are among key determining factors for people when choosing a place to live.

Plan updates should include greenway linkages, on-street facilities such as bike lanes and sidewalks, as well as off-street facilities such as bicycle and pedestrian connections between existing residential neighborhoods. Such a network should be implemented through the development process and as opportunities and funding arises through roadway projects or other capital funding.

Implement Transportation Demand Management (TDM) Measures

Transportation Demand Management (TDM) refers to a range of policies and programs to promote and incent the use of transit, carpooling, telecommuting, walking and bicycling and discouraging the use of single-occupancy vehicles for trips. TDM measures are most often managed and implemented by employers, universities, or public agencies.

Employers and universities across the county have found that paying employees the equivalent cash benefit of parking charges to not drive to work actually is cheaper than paying to provide employee parking. Furthermore, it reduces the number of employees who choose to drive alone to work and therefore increases the number of employees who chose other options including active modes. By providing incentives not to drive and increasing the cost of parking, communities and employers actually free up land for more productive development.

It is imperative to facilitate coordination measures between, Cities, Counties and major employers such as hospitals, military bases and educational institutions to promote and provide incentives for carpooling, park-n-rides, telecommuting and bicycling and walking. These entities might consider jointly funding a staff person whose job it would be to coordinate such efforts.

Revise and Enhance Transportation Impact Analysis (TIA) Requirements

A Transportation Impact Analysis (TIA) is a specialized study that evaluates the effects of a development’s traffic on the surrounding transportation infrastructure. It is an essential part of the development review process to assist developers and government agencies in making land use decisions involving annexations, subdivisions, rezonings, special land uses and other development reviews. The TIA helps identify where the development may have a significant impact on safety, traffic and transportation operations, and provides a means for the developer and government agencies to mitigate these impacts. Ultimately, a TIA can be used to evaluate whether the scale of development is appropriate for a particular site and what improvements may be necessary, on and off the site, to provide safe and efficient access and traffic flow.

Many of the observed and stated transportation issues in our region relate to the level of motor vehicle congestion and traffic, the realistic solutions will have to include compact, mixed-use development; promotion of modes of transportation such as carpooling, telecommuting, and other measures to manage the demand for roadways; and provision of high quality transit and bicycle and pedestrian mobility options. The opportunities for building roadway capacity and networks to mitigate congestion are very, very limited; costly; and long term solutions. Regardless, roadway projects do not always solve congestion problems; they may just defer them to a later date or another location and often actually induce more motor vehicle travel.

Numerous policies are available to expand transportation choices, and a number of them are featured in this section as a means to help communities identify opportunities to enhance their transportation network. Like the others presented in this toolkit, these policies are best used in combination with parallel policy efforts to support other aspects of sustainable growth.

Finance and provide incentives for multimodal transportation systems that include supportive land use and development.

States are responsible for much of the nation’s transportation planning and investment. As a result, states can directly affect the mix of transportation modes available by planning and funding a balance portfolio of pedestrian, auto, transit and bike transportation facilities. The effectiveness of these investments however, is greatly dependent upon the existence of supportive land uses. For example, sidewalks without nearby destinations render walking an unrealistic option; transit servicing of low-density areas is expensive, and land uses that separate residential development from jobs and shopping increase congestion.

States can improve the cost-effectiveness of their transportation investments by ensuring that transportation and development are coordinated. Project selection criteria should give priority to those projects that demonstrate supportive land uses. Examples include transit service for areas with transit-oriented development or bikeways connecting residential areas with shopping and amenities. By including a commitment for follow-up implementation funds for the transportation portions of the plan, states can use special grant programs as catalysts for integrated land-use transportation planning by local governments. Requirements or incentives for land planning can be implemented in areas where major expansions or new facilities are contemplated. States can also offer incentives and reward to communities that ensure safe-routes to school and to communities that locate schools in walkable locations.

Communities can take advantage of the flexibility in federal transportation law to create public-private partnerships around transportation and development investments. For example, they can use transportation fund for brownfields redevelopment or take advantage of joint development policies to encourage transit-oriented development. Finally, state transportation departments can encourage their own offices and local governments to adopt policies that allow flexibility in road, pedestrian, bike and transit facility design standards, such that upgrades and new facilities fit the character of existing communities.

Make sure transportation models and surveys accurately reflect all modes of transportation

Sustainable growth planning relies on forging good connections between development projects and transportation networks. Good planning relies on good predictions, and for predictions, planners turn to survey data, trend analysis, and computer models. Unfortunately, the methods used in trend analysis and computer models often only estimate automobile-related outcomes and design strategies. Thus, trips made on foot or by bicycle are underestimated or discounted. As a result, conventional modeling results tend to overestimate traffic and parking requirements for sustainable growth projects. They also tend to underestimate the benefits that can accrue from improvements to the pedestrian, bicycle, and transit system.

On a larger scale, transportation models are used to plan regional transportation projects and to ensure compliance with air-quality regulations. As with any form of modeling, a range of assumptions, such as 20-year employment forecasts and population statistics, is used to fill in the knowledge gaps. Assumptions used in transportation/air-quality models are based on typical development patterns, such as separated uses, a single mode of transportation, and a hierarchy of streets. Communities trying to comply with pollution reductions face limited options tied to the modeling and what it measures, such as carpooling or vehicle flee mixes, and often do not consider development patterns that encourage walking or biking. Because the transportation performance of sustainable growth decisions cannot be credited under conventional models, local governments have fewer incentives to adopt sustainable growth policies

To better determine the transportation performance of sustainable growth projects and plans, models need to measure the effects of transit, walking and bicycling on air quality. A set of data is emerging on the transportation and environmental performance of transit-oriented development, community design, and supporting policies. Many localities would appreciate a system that gives regulatory credit for the air quality benefits of sustainable growth, but are unsure how to account for the cumulative performance of numerous small projects over time. The Clean Air Counts Project in Chicago, www.cleanaircounts.org, provides a good example of how to account for the air-quality benefits of numerous small actions. In an effort to lower ozone levels, the city sponsors a web site that allows commercial painters and homeowners to enter how many gallons of low-VOC (volatile organic compounds) paints they have used. The city then tabulates the reduction in VOC levels compared with estimated levels of using conventional, higher-VOC paints. In the same manner, regions could account for the environmental performance of transit-oriented development (TOD) compared with the air-quality profile of a similar intensity of development under a conventional, non-transit-oriented plan.

Address parking needs and opportunities

Parking – its provision, pricing and distribution – plays an important role in creating a balanced transportation system. The availability of parking at local destinations influences an individual’s choice to walk, bike or take transit. Parking requirements affect the financial viability and form of specific development proposals and, in turn, affect the ability of those developments to play a supporting role in a multimodal transportation system. For instance, requiring large amounts of parking for a transit-oriented infill development drives up the cost of the development and may undermine the ability of the development to support transit.

Communities can affect change in the way parking influences transportation choices through a range of potential efforts. They may choose to allow on-street parking to meet parking requirements, or they may reduce the amount of parking required for infill sites in mixed-use or transit-oriented areas. They may work with employers to create priority parking areas and to reduce parking fees for carpools, allow employees to “cash-out” their parking benefits, or tax as income parking benefits that workers receive. Communities may encourage developers either to locate parking behind building in garages or in courtyards rather than in surface parking lots in front of buildings. Surface parking can also be designed to appear more like a park, courtyard, or plaza that doubles as public space in off-peak hours. Jurisdictions may design public parking garages as mixed-use buildings with storefronts that match neighborhood commercial buildings. They may allow local businesses to fulfill their parking requirements by purchasing credits for garage spaces or by sharing parking if peak hours are different. Communities can work to ensure that parking is located in areas that serve residents and businesses throughout a district. Finally, parking can be located to allow drivers to access pedestrian networks once they have parked, so that they can access a day’s worth of activities on foot. These options are just a few of the many ways that communities can improve their treatment of parking.

Plan and permit road networks of neighborhood-scaled streets (generally two or four lanes) with higher levels of connectivity and short blocks.

Overreliance on hierarchical street networks composed of neighborhood, collector, arterial, and freeway roads tends to force traffic onto a small number of major roads, which provide drivers with few alternate routes in the event of congestion or accidents. Also, because major roads concentrate traffic, they generally do not provide a good environment for pedestrians or residential development. The result is that these corridors are generally accessible only by car.

A finely woven network of smaller streets can move large volumes of traffic, provide routing redundancy, and help drivers avoid long delays associated with the left turns at large, multilane intersections. These streets also are scaled to the neighborhood level. Narrower than major roads, such streets generally have slower speeds that are compatible with a mix of residential, commercial and retail uses. This mix of uses and improved connectivity makes walking a realistic transportation option because destinations can be placed at closer distances, and more direct routes exist for pedestrians to reach a given destination. In addition, unlike major thoroughfares, large setbacks are not necessary to shield building occupants from the noise associated with large volumes of fast-moving traffic.

Improve roadway connectivity standards

Improving connectivity and limiting cul-de-sacs results in improved mobility for motorists, pedestrians, and cyclists; decreased response time for emergency services and delivery costs for services such as garbage collection through improved routing options; and, improved water pressure and maintenance from the ability to loop lines through a development rather than have to rely on less efficient dead-end pipe runs.

Traffic studies have shown that highly connected street networks provide much greater traffic capacity and mobility for a community at less cost. A high degree of connectivity should occur not only at the level of thoroughfares, but also on collector, local and other secondary roads. Such connectivity vastly improves a street network’s performance.

Definitive standards should be established for the use of cul-de-sacs and other permanent dead end streets. Connectivity requirements should be objective, definitive and measurable. Block length and intersection spacing standards are arterials should be based on the context of development and density. In low density residential area, blocks may appropriately be 800 to 1000 feet. In highly compact, pedestrian environments, intersections should be spaced 200-400 feet apart.

Consult early with emergency responders when developing sustainable growth plans

One critical component of a community’s transportation system is effective emergency response. In some instances, fire, ambulance, or police officials have expressed concerns with sustainable growth neighborhood street designs because of access. Specifically, they are worried that narrower streets, smaller intersections, or shorter curve radii will make turns difficult or will impede staging activities – particularly as the equipment used gets larger. In some instances, communities have abandoned plans for sustainable growth road and transportation improvements, such as multiuse streets or engineering techniques to calm traffic after fire chiefs have testified against the plans based on accessibility concerns.

To achieve safer street networks, local governments should consult emergency responders during the design phase of a road improvement project instead of at the end of the process. By working together ahead of time, local governments and emergency responders can create designs that result in safer, more livable communities. For instance, by consulting with emergency teams on fire equipment staging requirements, road designers can create midblock bulb-outs that provide adequate space for staging, parking can be moved further back from crucial intersections, and shoulders and curbs can be designed for emergency equipment use.

Connect transportation modes to one another

Too often, transportation systems and networks are planned and operated in an uncoordinated manner – both within and between jurisdictions. Providing efficient connections between difference modes is key to achieving a functioning multimodal system. For instance, nearly every transit trip starts or ends with a pedestrian trip. If the pedestrian fails to connect well with the point of transit pickup (no sidewalks leading to the stop, long walks, or wide roads to be crossed), transit is much less convenient, accessible, and competitive. All transportation options become more viable when they are connected to other modes. For example, bike racks at transit stations create a wider ridership for transit by effectively extending the range passengers will travel. However, better still are transit systems that allow bikes on board because they extend the area of origin and destination. Similarly, auto trips can be more effectively linked with pedestrian transportation when destinations are close to one another and walkways are provided between locations.

Zone for concentrated activity centers around transit service

To be most effective, transit service requires supportive land use. Local governments can help to ensure good accessibility to transit by clustering higher-density residential development around transit stops. Some researchers estimate that a minimum of six to eight residential units per acre are needed to support basic transit service provision. In addition, transit becomes still more effective if other services and amenities are also co-located with transit. Such services and amenities include community services such as childcare, as well as facilities for daily trips such as dry cleaning, parcel pickup and drop off, and convenience store shopping. Enabling transit riders to accomplish multiple errands as part of their commute is essential if public transit is to become a viable, convenient transportation option.

Adjust existing transit services to take full advantage of transit-supportive neighborhoods and developments

Coordinating land use with transit is often considered in the context of future developments and new transit service. However, powerful opportunities may exist within the context of the current transit system. Local governments can evaluate existing systems and relocate routes or stops to ensure that areas with high densities, good mixes of use, and high-quality pedestrian access are well served by transit. In addition to locating transit in areas with supportive land uses, local governments can also target transit based on economic and demographic factors. For instance, neighborhoods with higher percentages of young people, students and elderly citizens my yield higher riderships, and strategic routing decisions can help to ameliorate the effects of regional and subregional jobs-housing imbalances. To be most successful, the nature of commutes and other trips – reverse commutes, weekend service, employee job travel, and entertainment trips – should be considered to determine timing and fare schedules.

Create comprehensive bicycling programs

Even though the use of bicycles for commuting and running errands is increasing, the percentage of trips made by bike are still small. According to a 2003 poll sponsored by the American League of Bicyclist, 52 percent of Americans would like to bike more often. Three-quarters of those polled said that providing safe bike paths and other amenities would prompt them to bike more.

A comprehensive bicycle program can create the conditions for bicycles to be a competitive transportation option. A good plan considers all points in the trip, including the destination point, and provides safe and convenient routing and facilities. Bicycles are made still more viable as transportation options when they are integrated and coordinated with other modes. For instance, in some communities transit authorities place bike racks strategically for maximum use, both on buses and rail cars as well as in transit stations with lockers and near connecting lines. Recreational trails are increasingly being viewed as transportation facilities, designed intentionally to connect housing with services, entertainment, and employment.

Require bicycle parking for new development

Improved access for pedestrians and cyclist to services, employment/education, recreation, and other destinations will contribute to the sustainable growth movement. For bicycles specifically, access alone is not enough. Like motorists, cyclists need a safe and convenient place to park their vehicle at their destination. One of the biggest deterrents to people riding to their favorite destination is “fear of having a bicycle stolen.” Providing bicycle parking also lets cyclists know that they and their bikes are welcome.

Just as the provision of motor vehicle parking has been shown to induce driving, the provision of safe and convenient parking for bicycles can have the same effect on bicycling. Bicycle parking can be provided at a fraction of the cost of automobile parking and in a fraction of the space. 10 to 12 bicycles can be parked in the area of one car parking space at a cost of tens of dollars per bicycle space versus hundreds or thousands of dollars per car space. Bicycle parking standards should meet the needs of both short term visitors and customers and long term employees, residents and students.

Require sidewalks in all new development

With the growing dominance of the automobile, many new streets are built without sidewalks. It is true that the existence of sidewalks will not create walkers. Other elements including a mix of uses, short blocks and nearby destinations are necessary to make walking anything but recreational. However, sidewalks are indispensable to this mix. They are essential to creating a safe and secure pedestrian environment, and therefore a balanced mix of transportation options. Local governments can require that new developments provide sidewalks so that residents and users of these developments can walk or bike if they choose. (See Principle 2 for further information on walkable/bikeable communities)

Create programs and policies that support car sharing

support car sharing

Car-sharing programs, which allow members to reserve a car from a fleet of cars for short periods of time, are ideal for people who need a car infrequently or for families who are not interested in owning more than one car. Programs are typically operated by private companies such as ZipCar, although San Francisco’s City CarShare is sponsored in part by local governments. In areas with a high share of alternative commuters, businesses can sponsor the practice so that employees who do not drive to work can share a car for lunchtime errands or emergencies. The Commuter Challenge in the Seattle area and Zev-Net in the Southern California are two programs that provide a fleet of cars for day use to commuters who do not drive to work. Businesses and local governments have also benefited from car-sharing programs by avoiding the costs associated with maintaining a fleet of cars to make client and service calls.

Car-sharing programs, which allow members to reserve a car from a fleet of cars for short periods of time, are ideal for people who need a car infrequently or for families who are not interested in owning more than one car. Programs are typically operated by private companies such as ZipCar, although San Francisco’s City CarShare is sponsored in part by local governments. In areas with a high share of alternative commuters, businesses can sponsor the practice so that employees who do not drive to work can share a car for lunchtime errands or emergencies. The Commuter Challenge in the Seattle area and Zev-Net in the Southern California are two programs that provide a fleet of cars for day use to commuters who do not drive to work. Businesses and local governments have also benefited from car-sharing programs by avoiding the costs associated with maintaining a fleet of cars to make client and service calls.

Car sharing supports sustainable growth by reducing the number of vehicle on the road, even as it offers the advantages of car ownership for people who do not want to own a car. It is estimated that each shared car replaces single ownership of up to six cars, which, by extension, reduces the amount of parking needed and therefore reduces potential development costs. Car sharing programs work best where there is a high density of residents, a variety of transportation options and limited parking.

Car-sharing programs can be encouraged through local policies that boost their appeal. For example, localities can reduce the number of parking spaces required for higher-density residential projects in exchange for a highly visible, preferred parking space for a shared car decorated with the car-sharing program’s logo. Local governments can also assign certain public spaces, either on or off-street, for a car-sharing fleet. Regional authorities can also recognize car sharing in their transportation and air-quality programs.

Car-sharing programs can be encouraged through local policies that boost their appeal. For example, localities can reduce the number of parking spaces required for higher-density residential projects in exchange for a highly visible, preferred parking space for a shared car decorated with the car-sharing program’s logo. Local governments can also assign certain public spaces, either on or off-street, for a car-sharing fleet. Regional authorities can also recognize car sharing in their transportation and air-quality programs.

Collaborate with employers and provide information and incentives for programs to minimize or decrease rush-hour congestion impacts

Daily travel patterns are the result of thousands of individual travel decisions on the part of community residents. Employers are one way to reach those individuals and influence their decisions. Regardless of local and state government efforts to manage traffic more effectively, employers are increasingly finding strong business reasons to work with their employees on transportation issues. Employee retention and lost productivity are just two of the reasons for employers’ interest. In Atlanta, Bell South’s concern over its employees’ rising commuting difficulties led them to consolidate more than seventy offices into three locations – each immediately adjacent to a subway stop.

Local government can play an important role in increasing employer efforts by providing information and incentives for employer-sponsored commute options. Subsidies for use of public transit and employer-assisted housing programs for employees who live near their jobs can help minimize rush hour congestion by vehicles. Additionally, included in the range of transportation choices is the option to remain in place. Private employers who provide opportunities for employees to work at home through tele-commuting, or condense work hours via flex time can facilitate this choice.

A wide variety of resources and programs are available to help the San Joaquin Valley region expand its possibilities to provide a variety of transportation choices. The following listing contains relevant programs, resources and contacts for technical assistance, financial tools and specialized expertise available locally, as well as at the state and national level.

§ List here (to be inserted at a later date)

§ List here (to be inserted at a later date)