As Americans, we are consuming more land than ever before. During the last two decades of the 20th Century, Americans developed land three times faster than we grew as a nation. According to a Brookings Institution Survey Series, the amount of urbanized land used for development increased by 45 percent from approximately 51 million acres in 1982 to 76 million acres in 1997. The population grew by only 17 percent during this same time period.

Sustainable growth provides a means for communities to incorporate more compact building design as an alternative to conventional, land consumptive development. Compact building design suggests that communities be designed in a way which permits more open space to be preserved, and that buildings can be constructed which make more efficient use of land and resources. By encouraging buildings to grow vertically rather than horizontally, and by incorporating structured rather than surface parking, communities can reduce the footprint of their new construction and preserve more greenspace. Not only is this approach more efficient by requiring less land for construction, it also provides and protects more open, undeveloped land that would not exist otherwise to absorb and filter rain water, reduce flooding and stormwater drainage needs, and lower the amount of pollution washing into our streams, rivers and lakes.

Baker Place, San Jose – Four affordable units per grand house

Compact building design is necessary to support wider transportation choices and provides cost savings for localities. Communities seeking to encourage transit use to reduce air pollution and congestion recognize that minimum levels of density are required to make public transit networks viable. Local governments find that on a per-acre basis, it is cheaper to provide and maintain services like water, sewer, electricity, phone service and other utilities in more compact neighborhoods than in dispersed communities.

Compact building design is necessary to support wider transportation choices and provides cost savings for localities. Communities seeking to encourage transit use to reduce air pollution and congestion recognize that minimum levels of density are required to make public transit networks viable. Local governments find that on a per-acre basis, it is cheaper to provide and maintain services like water, sewer, electricity, phone service and other utilities in more compact neighborhoods than in dispersed communities.

Compact development is the strategy of increasing the density of urban areas while adding amenities that make them more livable. For example, a key assumption of compact development is that by using less land area for buildings and roads, more open space can be set aside, for parkland or agricultural uses. Compactly designed communities can provide more housing choices, support alternative modes of transportation, create walkable communities, and allow services to be located nearby. Compact building strategies include multistory buildings, use of parking garages instead of surface parking, and clustering buildings. This approach helps address the crucial problem of affordable housing. By offering greater convenience, less need for driving, and pedestrian-friendly environments, compact developments are more human-centered and less car-centered. Compact developments achieve the population densities needed to support viable alternative transportation systems such as trains, buses and taxis, bike trails and foot paths.

Compact developments result in smaller areas of impact, make more efficient use of utilities and infrastructure such as roads, reduce consumption of land, and can result in significant energy savings, as well as tax savings due to reduced infrastructure construction and maintenance.

Compact building design works because:

- An equal or greater number of units can be built on smaller lots

- More housing at a variety of prices is possible

- More acreage of open space is conserved

- Open space and parks make developments more attractive

- Wildlife benefits from land conserved as open space

- Lower infrastructure costs due to fewer roads, shorter lengths of water, sewer and utility lines

- More pedestrian friendly, resulting in less traffic

General compact building design strategies include:

Encourage greater development density

One of the most important opportunities for the San Joaquin Valley region given the high cost of land and the sensitive environmental conditions is to use the most buildable land more efficiently by building more compactly and more vertically. Compact developments can help the San Joaquin Valley region achieve many of its other sustainable growth goals.

Higher density development:

- Is a key element to creating walkable/bikeable communities

- Provides more transportation options

- Contributes to a wider range of housing choices along with more affordable options

- Generate less stormwater runoff

Concentrate commercial development in mixed-use nodes

Focusing commercial development to pre-automobile era standards provides for multi-block nodes consisting of multiple uses in an area designed to be covered on foot. Consolidating our commercial zoning into nodes of mixed-use districts conducive to pedestrian friendly access preserves open space and reduces our carbon footprint.

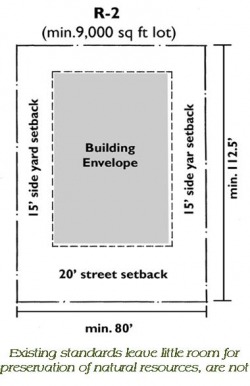

Reduce setback/dimensional standards

The limited approach to setbacks provides little room for the preservation of natural resources. By bringing buildings closer to the sidewalk, the street becomes more pedestrian-friendly providing a greater sense of enclosure and security and enables easier interaction. Reducing minimum lot size, lot width, and setback dimensions can encourage the development of townhouses, multi-family and small lot single family dwellings on infill lots in or near downtown and identified mixed-use nodes. This places higher density areas within walking distance to amenities and services.

Use density-based districts

A better and more flexible tool than minimum lot sizes is the application of maximum permitted density. Density-based zoning achieves the goal of limiting development density by district, but permits variety in lot sizes and housing types based on market conditions and environmental conditions. Base densities can aid in neighborhood design by permitting (but not necessarily requiring) a variety of lot sizes within close proximity while regulating the actual number of units that impact surrounding infrastructure.

Update density and height requirements

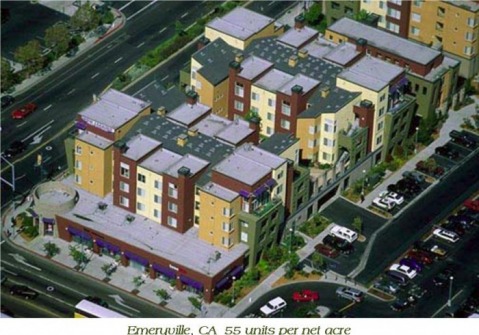

Emeryville, CA 55 units per net acre

Most Unified Development Ordinances include various restrictions on the mass and height of buildings. When combined with relatively large minimum lot sizes, these regulations result in a land use pattern that is inefficient and not at all compact. Consideration of increased allowable building heights should be considered in identified mixed-use nodes. A minimum number of stories or minimum Floor-Area-Ratio (FAR) may be appropriate in some areas to achieve the desired building and density patterns.

Most Unified Development Ordinances include various restrictions on the mass and height of buildings. When combined with relatively large minimum lot sizes, these regulations result in a land use pattern that is inefficient and not at all compact. Consideration of increased allowable building heights should be considered in identified mixed-use nodes. A minimum number of stories or minimum Floor-Area-Ratio (FAR) may be appropriate in some areas to achieve the desired building and density patterns.

Use density bonuses

Communities across the county are using density bonuses as a way to achieve community objectives while at the same time increasing development rights. There are numerous objectives for which density bonuses can be offered as incentives:

- Provision of affordable housing

- Provision of publicly available parking

- Provision of publicly available open space

- Provision of public art

- Conservation of natural areas beyond what is required

- Achieving certain green building standards, including reduced water

consumption and advanced stormwater management - Historic preservation of buildings and/or facades

Locate highest density residential near existing and future mixed-use centers

The normal order of density progression is to concentrate people and activities closer together at the town center and other mixed-use centers to provide efficient service and encourage a healthy, vibrant pedestrian environment. The best locations for high density developments should be evaluated in the context of an overall community master plan effort.

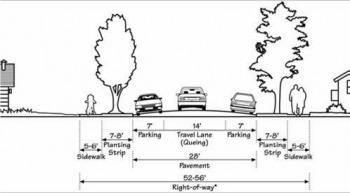

Revise Parking Standards

Parking requirements are one of the most ubiquitous deterrents to compact building development and walkability in American communities. Area devoted to parking is usually more than double that devoted to building on commercial properties. Studies have shown that typical commercial parking lots are grossly overbuilt. Strategies to reduce parking impacts include:

- Reduce parking minimums; apply parking maximums

- Require less parking in walkable, mixed-use area

- Require less parking in areas with transit service

- Require less parking for residential uses designed for seniors, low-income or disable individuals

- Count on-street parking towards the minimum required

- Provide density credits for publicly available parking in downtown and mixed-use areas

- Provide incentives for greater use of shared parking

- Require bicycle parking

Revise screening/buffer standards

A buffer requirement is a blunt instrument and a suburban standard, applied too heavily and broadly in too many contexts. Office, institutional and compatibly scaled multi-family developments can function without buffers between them. Screening requirements do provide beneficial greening, they can also increase the distances between land uses and restrict the ability to create compact, mixed-use centers. Context-based building and site design standards are a much more precise and appropriate way to deal with land use compatibility

Use public meetings about development options to educate community members on density and compact building options

Local government officials and developers who propose compact development face opposition from a public that is unfamiliar with high-quality compact development. To make sustainable growth work, the public will need to see how good design and compact building will create communities with convenience, privacy, recreation, and manageable traffic. Public involvement and education at the beginning of the process is the key to reducing citizens’ resistance to compact neighborhoods.

Visual imagining is one technique to help residents and developers on the demand for and benefits of compact communities. A perception exists among builders and developers that people prefer low-density developments. Visualization technology can be used at public meetings to gauge a citizen’s interest in a variety of development options or to help community members envision changes to an existing street by modifying a scanned photograph. Such opportunities represent an important learning tool in which community members begin to realize that the determinant of whether or not they favor a type of development is often not how dense it is , but how well designed it is. The Local Government Commission in California helps communities create these “community Image Surveys” to educate their citizens about issues related to planning and design. Private planning consultants offer similar types of visual preference tools. By using tools that focus on the impacts and benefits of the alternative development approach, local communities can overcome much of the uncertainty and lack of familiarity among citizens regarding compact communities.

Employ a design review board to ensure that compact buildings reflect desirable design standards

Attractive design is critical to balance the many competing demands placed on compact building design for efficiency, privacy and accessibility. A design review function can be a means not only to preserve the community character that exists, but also to ensure that new development reflects an appropriate and complimentary style. Use of a design review board can help alleviate fears of compact building design and help interpret a community’s preference for new development. As a result, review boards can help ensure that any amenities received from developers in exchange for incentives are well-designed assets to the community. Design review is found in most historic districts, but a community need not have a historic designation to benefit from this process. Developers can also benefit from a well-executed design review process because it can reduce the time and uncertainty of the project approval process.

While design review can help ensure that the proposed projects meet the community’s vision for how it wants to grow, it cannot take the place of inadequate or poor planning and zoning. It is important that concurrence between the planning and zoning already exist and that they both reflect the community’s wishes. Since value judgments are inherent in the design review process, it is critical that all potential stakeholders are represented in the review board and that the guidelines developed by the review board are approved by interested members of the community.

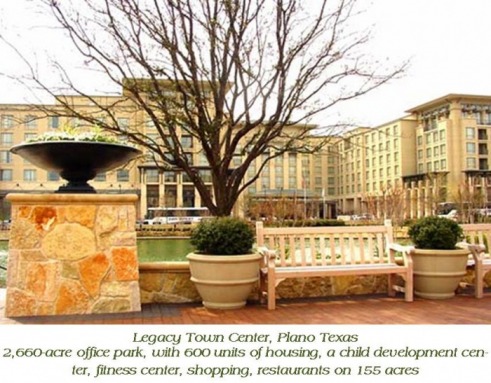

Create compact office parks and corporate campuses

In many areas, office parks are isolated pods of commercial or industrial development surround by grass or trees and parking lots that are linked to other office buildings by winding service roads. Disconnected from any community fabric, these places require that workers get into their cars to get lunch or run errands.

Separating office activity from residences and commercial areas can create a jobs-housing imbalance. The consequences of this are readily apparent: commuters spend hours in traffic to reach isolated office destinations, arterial roadways are jammed at lunchtime and workers have no nearby amenities. To deal with these issues and to create a more inviting environment for employers and employees, companies are looking at more integrated approaches to office parks. They are connecting job centers to nearby train stations with feeder buses. Office parks are becoming places where people can live and shop as well as work. Rather than building detached, single story office buildings, companies are seeing the advantages of locating in more compact areas that support a range of amenities.

Match building scale to street type in zoning and permit approval processes

Communities can highlight more opportunities for compact building design by creating stronger links between street widths and building scale. People feel more comfortable in neighborhoods in which buildings and landscape properly frame the street area. Buildings that are closer to the lot line, frame a street and calm its traffic, making it more pleasant to walk along. A similar relationship exists for buildings lining large arterial roads. A wide boulevard that currently accommodates one-story buildings along each side may become more visually pleasing and well-proportioned if four-story buildings line it instead. By clearly defining this valance between street type and building scale, a community can encourage more compact communities and better absorb new growth and development.

Rezoning existing commercial strips to require taller buildings on a street rather than large parking lots is a good start for rebuilding declining commercial strips into vital town centers. Not only does this strategy transform inhospitable pedestrian environments, but it also creates more space for office, residential, and retail uses. When more people and uses are drawn to an area, they create a pleasant, walkable environment that offers a sense of place and increases demand for stores, restaurants, offices and homes.

Ensure that big box stores coming to existing urban centers are appropriately scaled and designed

Big box stores are popular shopping destinations for American consumers. Large inventories and low prices tend to drive the demand. Architecturally, these stores are typically characterized by windowless, standardized, one-story buildings with an ample supply of parking.

Barnes and Nobles, River Park Place

It is crucial for communities to thoroughly review the pros and cons of big box retailing, including the impacts they may have on small businesses as it is clear that consumers have an appetite for them. While most big box establishments are located in the urban fringe, residents in urban areas are increasingly looking for compact versions of these big box stores. By encouraging these national chains to locate in older retail districts rather than suburban greenfields, it is possible to draw more customers to our downtown areas.

To make Main Street big box retail successful, communities need to ensure that new stores complement the existing retail district. There are design techniques that local governments and agencies may want to consider:

- Prohibit blank walls. Allow no uninterrupted length of any façade in excess of 100 horizontal feet. If a façade is greater than 100 feet in length, it must incorporate recesses and projections along at least 20 percent of the length of the façade. Windows, awnings and arcades must total at least 60 percent of the façade length abutting a public street.

- All facades of a building that are visible from adjoining properties or public streets should contribute to the pleasing scale features of the building and encourage community integration by featuring characteristics similar to a front façade.

- Do not locate more than 50 percent of the off-street parking area between the front façade of the building and the primary abutting street.

Use density bonuses to encourage developers to increase floor-to-area ratio

Density bonuses can promote many sustainable growth features in communities while also creating the land-use intensity that more efficiently supports public services. Density bonuses have been used to provide a variety of amenities including parks, plazas and structured parking. The basic premise is that a developer is granted the opportunity to increase the size of a building beyond that which is allowed by zoning, in exchange for providing a public amenity from which the community can benefit. The level of the bonus is designed to cover the cost of providing the amenity. In order for the community to get what it wants, this tool needs to be designed carefully. Explicit design standards, clear building criteria, and an engaged review board can ensure that the amenities are provided at the highest quality level. As a result of the use of density bonuses, not only do residents benefit from higher density development in targeted areas, but they also benefit from complimentary amenities that support a more compact community.

Ensure ready access to open space in compactly developed places

Useful urban green spaces are characterized both by parks used for recreation and by preservation areas use for habitat and environmental protection. Well-planned and well-maintained parkland is essential in sustainable growth communities where compact building design may reduce the size of private yards. Parks should be designed for a variety of people and purposes – such as civic plazas, formal gardens, children’s playgrounds, ball fields and regional parks. Open space in sustainable growth communities should also accommodate the ecological functions of undeveloped land, mature trees and natural migratory corridors. Urban green space can provide habitat protection for birds or small animal species, can host trees that provide shade and filter the air, and can help recharge drinking water aquifers. These open spaces are less formal, and their design will be dictated in large measure by their natural features.

The need for open space, sunlight and nature persists in all parts of a sustainable growth community. By clarifying the function and value of the open space created in compact areas, communities can meet the environmental and recreation needs of those who live, work and play there.

Encourage developers to reduce off-street surface parking

While compact building design can increase the viability of other modes of transportation, most communities are still highly dependent on the automobile and should therefore plan to accommodate parking. Conventional approaches to parking – particularly large surface spaces between the street and front door of the home or business – represent inefficient uses of valuable urban land and undermine the walkability that compact communities would otherwise support. These large paved surfaces increase the amount of stormwater that quickly runs off into storm sewers and surface water, thus increasing the risk of flooding and washing pollutants into our streams, rivers and lakes.

Communities can better plan for parking and reduce the need for surface lots by using several tools. They can allow on-street parking to qualify towards the amount of parking a building owner needs or encourage buildings that need parking at different times of the day to share parking spaces. Communities can work with employers to offer the option of financially compensating employees who do not use the company parking lot. They can also reduce many of the negative impacts of parking by building parking structures. As structured parking is more expensive than surface parking, localities may need to encourage its construction with financing incentives such as city funds, the use of special tax districts, or tax increment financing. In doing so, jurisdictions can free up valuable land in compact urban centers for property development which will generate tax proceeds, offsetting the additional costs.

Manage the transition between higher and lower density neighborhoods

Providing a variety of housing, neighborhood, and transportation choices is one of the goals of the sustainable growth principles. To provide choices, a variety of development – including main streets with shops and townhouses, business centers with offices and apartments, and single-family neighborhoods with yards – is needed.

Communities that successfully integrate higher and lower density development meet a variety of living preferences and economic means. Residents can choose to live in any number of amenity-rich neighborhoods that are a short walk or bike ride from shopping, parks, schools and restaurants and a short drive from work and regional destinations. Integrating density allows urban living to some and suburban living for others while increasing property values and maintaining community character throughout.

A few techniques available to manage the transitions between areas of lower density and areas of higher density include:

- Establish bull’s eye zoning around transit stations. This concentrates the highest density around the areas with the greatest transportation choices and gradually reduces density as you move away from the stations. In single-family neighborhoods, residents know that higher densities will be located elsewhere and that there will be developments of middling densities to transition from one neighborhood type to another.

- Stepping down building heights. Transitions between high density and low density are mediated by middling densities. Midrange densities can take different forms, such as large buildings surrounded by parking or smaller buildings that make up more coherent neighborhoods. Low-rise buildings achieve moderate densities, provide sound barriers between busy centers and quiet neighborhoods, and create visual progression.

- Citizen participation in the planning process. Citizen participation creates support for higher-density development in the transit corridor area and their input helps to ensure that new development adds value to existing neighborhoods.

There are many other techniques that can be applies such as: strategic location of parks, matching building types across streets, stepping buildings back when they reach their upper stories, and matching architectural styles.

Strategically reduce or remove minimum lot size requirements

When faced with traffic, loss of open space, or rising demands on public services from new developments, many communities seek to fix the problem by increasing minimum lot sizes. The thinking is straightforward. Larger lots mean more expensive houses which in turn generate more tax revenues. Spreading out development will spread out traffic and reduce congestion. Put the same house on a larger lot and leave more open space. There is an intuitive appeal to this thinking. However, many communities have had counterintuitive results, with large lot sized sometimes exacerbating the very problems they were meant to avoid.

While government requirements for larger lots do drive up housing costs, the extra tax revenues may be offset by other factors. For instance, longer distances between houses mean extra infrastructure and higher capital costs – not only within the development, where the developer pays, but also between developments where the local government will pay. Larger lots mean a development consumes more land than it would otherwise. When this land is farmland or “working land,” the locality loses a valuable taxpayer. Unlike houses, working lands almost always pay more in taxes than they demand in services. Zoning exclusively for large lots and houses may mean that more incoming households will be families with school-age children. Schools are often a local governments largest cost. Zoning that provides for families, retirees, young couples and singles can diversify the household base and reduce school costs.

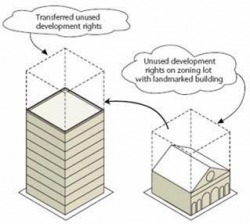

Localities are now looking at the advantages that can come with strategic reductions, or in some parts of a community, with the removal of minimum lot sizes. Smaller lot sizes can reduce market pressure on undeveloped land, providing communities with time to preserve important open space. One way to achieve this is through tradable development rights, where more building opportunities are provided in one area in exchange for preservation in another.

Ensure a sense of privacy through the design of homes and yards

Opposition to compact communities is sometimes based on the perception that buildings within these communities will be ugly and poorly designed and will offer little or no privacy for their residents. Certainly, the threat of poor design is not limited to compact buildings. Careful design can improve the relationship of the compact building to the community around it and serve the unique needs of those that reside and work within the community. When buildings are design appropriately, residents and building users can benefit from the amenities that accompany attractive, compact communities, without sacrificing personal privacy.

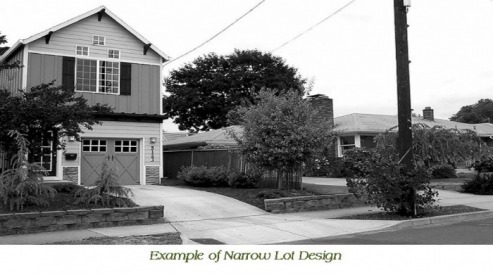

Well-designed projects balance both the need to engage the street, by having the primary façade “open” to the street, and the need to ensure a level of privacy for building occupants. Apartments can be designed to provide a center courtyard for residents to enjoy a sanctuary from the public. Narrow lot housing provides private spaces in side or back yards that offer a private refuge. Additional consideration in building construction can ensure that neighboring houses that overlook these private areas have windows mounted higher in the wall to allow light in while limiting views of neighbors’ yards.

Use compact design to create more secure neighborhoods

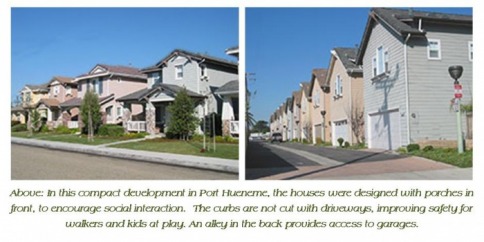

Well-designed compact developments can foster the sense of safety and security that every person desires n their community. By incorporating front porches, attractive common open space, and narrow streets with sidewalks into new or existing developments, the community promotes safety and security by means of its own activity. This type of crime prevention is referred to as “eyes on the street,” and is based on the idea that an active community with people using the streets and watching the streets from their homes or yard can deter street crime.

Neighborhood planners and community activists have begun to promote crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) in order to engage residents in endeavors to create safer communities. The establishment of defensible space, a key component of CPTED, occurs when community residents take an interest in their surroundings and adopt community policing initiatives. In an existing neighborhood, this means enacting traffic-calming measure and providing or enhancing semi-private courtyards to encourage residents to gather and monitor their surroundings. In proposed neighborhoods, streets should be narrow to encourage contact amount neighbors. CPTED uses design to minimize the opportunities for crimes to be committed.

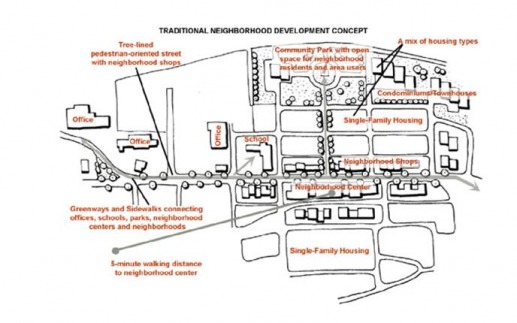

Use traditional neighborhood design

Mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly, compact developments are not new phenomena. These “traditional neighborhood design (TND) developments were the predominant urban form in the United States through World War II. After World War II, the predominant development pattern became single-use, low-density, auto-dependent designs characterized by pods of commercial, retail, office and residential development. The new form of development has replaced lively neighborhoods with stretches of residential, commercial and retail pockets. Within these contexts, compact development can impose unacceptable costs because the design, infrastructure, mix of uses, transportation options and other features that make density work well are not in place. Retrofitting existing neighborhoods and creating new ones with TND can help re-create functioning neighborhoods that benefit the economy, community and environment.

TND involves developing neighborhoods that have definite centers and edges, a mix of destinations within a short walk, a diversity of housing types and styles and access to public transit.

Offer incentives that encourage local communities to increase density

Local governments may avoid higher density development for fiscal or other reasons. State and regional governments can provide financial incentives to encourage local governments to approve compact building proposals with higher local densities. Financial incentives are a way to pass on to compact communities the cost savings that those communities generate for higher levels of government. Thanks to compact local design, the state and federal government pay less on a per unit basis for education, school busing, transportation, water and sewer services than they would under conventional development patterns.

The many sources of funding flowing from the state and regional governments include federal transportation funds, urban development block grants, and state income tax revenues to name a few. These funding sources can be allocated on a priority basis to compact communities thereby encouraging others to follow this example. As an example, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission awards bonus regional transportation dollars to communities that build high-density housing near mass transit facilities in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Support regional planning efforts to encourage compact communities

Residents are the best able to determine how and where their neighborhoods and communities grow. The impacts of these development decisions have a dramatic effect on regional growth, traffic congestions, environmental quality, and quality of life. Plans for incorporating higher densities into communities must be coordinated with transportation investments, parks and open space, and school planning. Communities can benefit from coordinating efforts at the regional level to identify areas targeted for more compact developments. By encouraging each locality to recognize both the local benefits and the regional implications of the approach, more support can be built across the region as a whole for compact communities.

Regional coordination can also help communities alleviate the concerns some residents may have about absorbing more than their “fair share” of the growth in the form of higher-density developments. The distribution of these clusters of development around the region, particularly when coordinated with regional transportation planning and transit nodes, can have a significant positive impact on open space preservation and air quality while also reducing traffic congestion. Regional coordination can also help tie the compact building decision of localities to the benefits, in the form of land preservation on the urban fringe, that these decision help achieve. These lands – whether they are used for agricultural or recreational purposes – provide economic and quality of life benefits to all members of the region. Making this link clear to area residents will help generate stronger support for creating more compact, vibrant communities.